Thursday 03 April 2025

- Thought Leadership

UK Economic Conditions Report: March 2025

Summary

- Real GDP growth in the UK is likely to accelerate in 2025 (from a low base) but geopolitical risks such as a potential trade war with the US complicate the outlook.

- Consumer and business confidence indicators are near or below growth thresholds and private consumption is curtailed by elevated precautionary savings.

- Inflation has moderated until Q3 2024 but has moved higher in the final quarter of the year; further increases are likely.

- The Bank of England will continue to cut interest rates in 2025 but the pace will be slower than initially anticipated.

- Although the unemployment rate is rising and the number of job vacancies in the UK is falling, wage growth remains substantial.

- Companies’ operating costs will also rise because of higher national insurance contributions, an increased minimum wage and the phasing out of business rate relief.

- The number of business failures in England and Wales has decreased by 5% in 2024 while figures went up by 4% in the neighbouring EU.

- B2B payments performance in the UK has also improved last year but the fallout of the autumn budget and sizable geopolitical risks weigh on the 2025 credit risk outlook.

To view a pdf version, click here.

![]()

Economic Performance

The UK’s 2025 growth outlook continues to disappoint as confidence indicators are moving lower (or sidewards), trade tensions with the US escalate and the domestic labour market is cooling down gradually. As a consequence, the Bank of England has recently halved its 2025 real GDP forecast to now 0.8% only.

Consumer Confidence

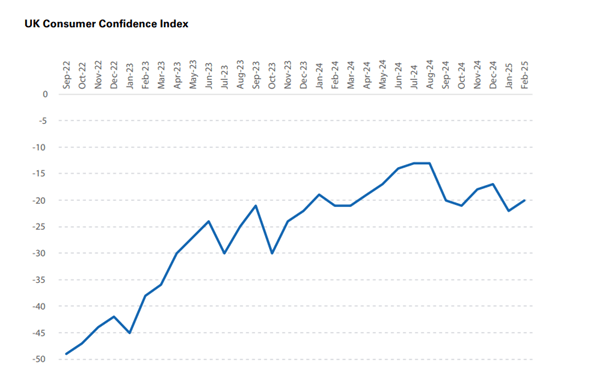

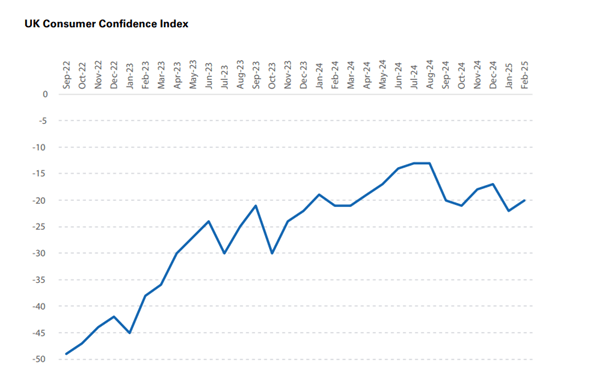

Following the Covid pandemic in 2020-21, British consumers were subsequently hit by record high inflation in 2022-23 (see inflation chapter below). As the cost-of-living crisis came to an end over the second half of 2023 and the first half of 2024, UK consumer confidence moved higher: from a very low minus 49 points in September 2022 to minus 13 points in mid-2024.1.

Source: NIQ GfK

Since then, the index has lost some ground though, falling to minus 21 points in October and subsequently moving sidewards, coming in at minus 20 points in February 2025. Looking at the latest data point, the “major purchase” sub-index has improved somewhat over the past twelve months (from -25 in February 2024 to -17 in February 2025) but British households have become even more pessimistic about the economic outlook: the “general economic situation over the next twelve months” sub- index has dropped from -24 to now -31 points.

Equally problematic for companies operating in the British B2C market, households’ savings rates have increased over the past years as consumers have ramped up precautionary savings amidst the sluggish economic performance. In Q3 2024, the households’ savings ratio (in % of post-tax income) stood at 10.1%, up from 7.9% one year earlier2 . Data from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) also shows that savings ratios are currently around twice as high as in 2017-19.

Source: ONS, note that mandatory lockdowns during Covid artificially inflated the 2020-21 readings

As British households continue to put more money aside (also driven by higher savings for retirement as the share of workers enrolled in defined-benefits company pensions has fallen from 3.6m in 2006 to under 1m in 20223), private consumption in the UK is likely to remain weaker than initially anticipated.

Business Confidence

Worryingly, industrial confidence indicators in the UK also disappoint at the moment. In the construction sector, the Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI, compiled by S&P Global) fell to 44.6 points in February. This is down from January’s 48.1 points and considerably below the neutral 50-points line that divides sectoral expansion from contraction4. All three sub-sectors (residential, commercial and civil engineering) stand in contraction territory and the February-reading was the lowest value in nearly five years. Worryingly, new order inflow also dropped to the worst reading since May 2020 (when Covid lockdowns were in place). Positively, UK construction companies still remain fairly optimistic about the year ahead. While 17% of all survey respondents count on falling construction sector output in the twelve months ahead, 39% forecast an improvement. That said, the corresponding readings compare unfavourably against their 2024-averages, also showing more widespread pessimism in the sector.

Source: S&P Global

In the manufacturing sector (which accounts for around 17% of UK GDP), confidence indicators have also deteriorated quickly in early 20255. The corresponding PMI dropped to 46.9 points in February, down from 48.3 points in January. Worryingly, the PMI has been below the neutral 50-points line for five consecutive months now and new order inflow points towards further challenges ahead. The output sub-index has been in contraction territory for four months in a row now and the employment subindex has fallen to the weakest reading since May 2020. That said, business optimism in the sector has improved to a six-month high in February but with potential tariffs on the horizon, it remains unclear whether this optimism is justified.

Meanwhile, the UK service sector (equivalent to around 80% of British GDP) continues to perform somewhat better. Service sector PMI came in at 51.0 points in February, up from 50.8 points one month earlier6. The PMI has remained in growth territory for the sixteenth month running but the most recent reading was below the long-run series average of 54.3 points.

Problematically, new order inflow fell for the second consecutive month (and by the fastest pace in more than two years), indicating increasing weaknesses of sales pipelines.

Similar to the developments in construction and manufacturing, service sector companies see more persistent pressures on input costs with around one-third of survey respondents reporting an increase in the average cost burden (only 2% saw a drop). As wage growth remained substantial (see Labour Market chapter below), the employment sub-index saw a sizable deterioration as well, coming in on the weakest reading since November 2020. While the majority of survey respondents still expects an improvement in business activity over the next twelve months, the corresponding sub-index has fallen to the lowest reading since December 2022. Companies are especially worried about the impact of incoming changes to the minimum wage and national insurance contributions, as laid out in the government’s Autumn Budget 2024.

Real GDP Forecasts

Economic data from the ONS mirrors the generally disappointing confidence indicators. In Q4 2024, real GDP growth in the UK came in at a low 0.1% quarter on quarter (q/q), thereby bringing the 2024 growth rate to 0.8%7 . Although this is twice as high as in 2023, the British economy continues to perform disappointingly with manufacturing seeing another contraction: while service sector output expanded by 1.3% last year, manufacturing witnessed a 1.7% drop. Construction and agriculture reported output growth of 0.4% and 1.0%, respectively.

Looking ahead, the 2025 outlook is clouded by both domestic and international developments. In its Autumn Budget in October 2024, the British government announced an increase in national insurance contributions plus a higher minimum wage. Both changes will come into effect in April and are likely to have negative effects on business investment and the domestic labour market. Meanwhile, lacklustre performance in the euro zone, the UK’s biggest trading partner is also having an adverse impact on the British economy. Germany, the bloc’s biggest economy has seen a second annual drop in real GDP in 2024 and is set for a difficult 2025.

Source: OECD and IMF

The biggest external threat to economic performance in the UK comes from the other side of the Atlantic though. Trade tensions with the Washington have escalated in early 2025 and the new US government has threatened to increase tariffs on British exports. As exports to the US accounted for 22% of all British exports in 2023 (making the US the second most important market, after the EU), exposure risks are sizable, according to the Bank of England’s (BoE) latest Monetary Policy Report8. Positively, 70% of British exports to the US are services which would not be directly impacted by tariffs on goods. That said, restrictions on services are also possible.

Although it remains unclear when tariffs are increased by the US government and whether the UK would be targeted, the general economic uncertainty arising from the erratic policy making in the US will have a negative impact on the UK’s growth outlook as companies are likely to postpone investment decisions. Also problematically, economic indicators in the US have also deteriorated in February and the country could fall into a recession over the next months, thereby clouding global as well as British growth prospects9.

As a consequence of the generally elevated level of economic uncertainty at the moment, 2025 growth forecasts vary largely and are subjected to sizable ad hoc revisions. In January, the OECD and the IMF expected real GDP in the UK to expand by 1.7% and 1.6% respectively but the BoE has halved its 2025 forecast to 0.8% only in February. Meanwhile, Consensus Economics (a publication that collects and aggregates projections from several professional forecasters) currently expects 1.4% growth but risks are tilted towards the downside.

Inflation

Positively, inflationary pressures continued to subside throughout much of 2024 and in September, the consumer price index including owner occupiers’ housing costs (CPIH) came in at 2.6%. This is the lowest reading since mid-2021 and down from the 41-year high of 9.6% in October 2022. The drop in inflation was mainly driven by the goods sector which was in deflation territory between April and October 2024. Meanwhile, the service sector continued to see more persistent, often wage-driven, price pressures, averaging 5.8% in 2024, almost three times the BoE inflation target of 2.0%.

Source: ONS

Worryingly, late 2024 has seen a modest return of inflation though. Between September and December, the CPIH increased from 2.6% to 3.5% before accelerating to an even higher 3.9% in January 2025, the worst reading in twelve months10. Consumer price inflation (which excludes owner occupiers’ housing costs) has increased from 1.7% in September to 3.0% in January 2025.

Looking ahead, the BoE expects inflation to remain on a bumpy path. Because of base effects and a change in regulated energy and water prices, consumer price inflation is likely to increase to 3.7% in Q3 2025 before moderating again11. As inflation will probably stay higher for longer, the BoE has also indicated that interest rate cuts will be smaller than initially anticipated. In a new set of forecasts, released alongside the Monetary Policy Report in February, the BoE announced that it expects its key policy rate to stand at around 4.2% in Q1 2026, up from a previously forecasted 3.7% and only marginally down from the current level of 4.5%12.

Labour Market

Unemployment

The UK labour market has cooled down somewhat in 2024, caused by weak economic growth but also because of higher wage costs (which has reduced labour demand). According to data from the ONS, the seasonally-adjusted unemployment rate stood at 4.4% in November 2024, up from 3.9% one year earlier13. However, despite the recent increase, unemployment is still low in an international comparison (unemployment in the neighbouring eurozone stood at 6.3%) and it remains close to the full-employment definition of 4%.

Source: ONS

During the remainder of 2025, unemployment is likely to rise moderately, caused by the effects of a higher minimum wage and increased national insurance contributions (coming into effect in April). That said, the anticipated increase will be rather small: in February, the BoE lifted its 2025 unemployment rate forecast in its Monetary Policy Report to 4.8%.

Vacancies

Unlike the unemployment rate, which had only started to deteriorate in 2024, the number of job vacancies in the UK has been on a deteriorating trend for several years already. During the Covid pandemic, job vacancies reached a multi-year low of 328,000 as many sectors went into lockdown14. After the reopening of the economy, vacancies surged to a new all time high of more than 1.3m in spring 2022. However, since then figures have started to come down again, dropping to 819,000 open positions in the three months to January 2025, comparable to the pre-Covid reading of 810,000 in Q4 2019.

Source: ONS

The job vacancy rate (which measures the number of vacancies per 100 employee jobs) has roughly followed this trend. The national average came in at 2.5 in the three months to January 2025, compared with 2.7 in Q4 2019 (and 4.2 in mid-2022). Over the past five years, retail (from 3.0 to 2.1), wholesale trade (2.7 to 2.0), accommodation & food services (3.7 to 3.3) and information & communication (from 3.1 to now 2.5) have seen a drop in vacancy ratios. Meanwhile, construction (from 1.7 to 2.6), manufacturing (from 2.1 to 2.4) and the public sector (from 1.8 to 2.5) have more vacant positions now than before the pandemic. Problematically, job vacancies are likely to fall further as companies’ willingness to hire should be negatively impacted by the incoming changes to national insurance contributions and the higher minimum wage.

Wage Growth

Meanwhile, salaries have yet to respond to the labour market slowdown, at least in real terms. In nominal terms, wages grew by a substantial 7.2% in 2023, also driven by record high inflation and tight labour market conditions15. In early to mid-2024, nominal wage growth has moderated, reaching 3.9% year on year (y/y) in June to August 2024, the lowest reading since autumn 2020. Since then, wages growth has accelerated again though, coming in at 6.0% y/y in Q4 2024.

Source: ONS

Meanwhile, real wage growth (nominal wage growth minus inflation) had been negative during the cost of living crisis in H2 2022 and H1 2023. After having turned positive in the three months to June 2023, it accelerated to a comparatively high 2.3% y/y March to May 2024. After a small deceleration during the summer months, real wage growth has now risen to 2.5% y/y in the final quarter of 2024, the highest reading since 2015 if the distorted Covid-pandemic period is ignored.

Looking ahead, wage growth is likely to decelerate in 2025, despite a 7% increase of the minimum wage in April (which will create upward pressure on salary structures). According to the latest BoE Monetary Policy Report from February, the softer labour market conditions should translate into nominal wage growth of 3.75% in 2025, lower than in previous years16. This would also have beneficial effects on inflationary pressures as salaries are a key input cost for companies, especially in the more labour-intensive service sector.

Credit Risk

Despite the relatively lacklustre economic performance in the UK, credit risk levels have improved in 2024. Against the wider regional trend, the number of business failures has fallen and average B2B payment delays have decreased, too. As real GDP growth will accelerate (albeit by a modest pace) and interest rates will continue to move lower, credit risk could see another improvement. That said, the uncertain effects of the Autumn Budget 2024 as well as the looming trade war with the US could have an adverse effect on payments performance and insolvencies.

Payments Performance

Positively, data from business information provider Dun & Bradstreet and its European partners shows that B2B payments performance in the UK has improved against the regional trend. Between Q4 2023 and Q4 2024, average payment delays (beyond agreed terms) fell from 13.0 days to 10.8 days in the UK. During the same period, the European average lengthened marginally by 0.1 days to now 12.2 days.

Source: Dun & Bradstreet

In a regional comparison, the UK is now ranked above the European average (for the first time in four years), only behind Germany (average payment delay in Q4 2024: 5.6 days) and the Netherlands (3.1 days). Since the start of the Covid pandemic in early 2020, payments delays in the UK have shortened by a sizable 3 days while France, the worst performer in this period, has seen an increase by 4 days (to now 16.6 days beyond agreed terms).

Business Failures

Encouragingly, the UK is one of a few select European states that has seen a drop in corporate liquidations in 2024. After hitting a thirtyyear high in 2023, the number of company insolvencies in England and Wales dropped to 23,880 in 2024. While this is down by 5% against prior year, it is still significantly above the pre-Covid reading of 17,171 insolvencies in 201917. Meanwhile, Northern Ireland has seen another increase in corporate liquidations last year (from 218 to 305) while Scotland saw a stagnation (1,236 failures in 2024 after 1,234 in 2023).

Source: UK Government Insolvency Service

Across the Channel, the neighbouring EU has seen another increase in company bankruptcy declarations in 2024. Compared against prior year, figures increased by 4% in the EU-27 (and by 6% in the eurozone). Worryingly, the bloc’s three biggest member states have all seen double digit growth: while insolvencies increased by 10% in France, Italy (+20%) and Germany (+22%) have seen even bigger deteriorations18.

Positively, the anticipated uptick in real GDP growth and the fall in interest rates, albeit both smaller than initially expected, could drive UK business failures lower. At the same time, increased wage costs, especially at the low-skilled end of the labour market, higher national insurance contributions and the phasing out of business rate relief will all increase UK companies’ cost base in 2025. That, coupled with sizable geopolitical risks such as a potential trade war with the US and the poor momentum in UK retail, following a disappointing Christmas period might increase the number of business failures.

Data for January 2025 shows that the year has started off on the wrong foot already: according to the government’s Insolvency Service, registered company insolvencies in England and Wales were up by 6% month on month and an even higher 11% y/ys19. Against this backdrop, counterparty risk should be monitored closely and appropriate action (such as tightening credit terms or leveraging trade credit insurance) should be considered.

[1] https://nielseniq.com/global/en/news-center/2025/consumer-confidence-up-two-points-in-february/

[2] https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/grossdomesticproductgdp/timeseries/dgd8/ukea

[3] https://www.investorschronicle.co.uk/content/5d4d918c-2568-59c3-b532-65613a960232

[4] https://www.pmi.spglobal.com/Public/Home/PressRelease/d22e0901f3704615b530235d9d83fe9f

[5] https://www.pmi.spglobal.com/Public/Home/PressRelease/dc0da0ebd96a4ee681ce79b16299171f

[6] https://www.pmi.spglobal.com/Public/Home/PressRelease/f6ca0b9fbf7a495e9b1326e558783baa

[7] https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/grossdomesticproductgdp/bulletins/gdpmonthlyestimateuk/december2024

[8] https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/monetary-policy-report/2025/february-2025#:~:text=UK%20GDP%20growth%20is%20estimated,0.4%25%20rates%20expected%20in%20November.

[9] https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cz61nn99eg1o

[10] https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/inflationandpriceindices/bulletins/consumerpriceinflation/january2025

[11] https://www.reuters.com/world/uk/uk-inflation-hump-unlikely-lead-long-term-price-pressures-boes-mann-says-2025-03-06/#:~:text=The%20Bank%20of%20England%20forecasts,monetary%20policy%20should%20remain%20restrictive.

[12] https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/monetary-policy-report/2025/february-2025

[13] https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmentandemployeetypes/bulletins/uklabourmarket/february2025

[14] https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmentandemployeetypes/bulletins/jobsandvacanciesintheuk/february2025

[15] https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmentandemployeetypes/bulletins/averageweeklyearningsingreatbritain/february2025

[16] https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/monetary-policy-report/2025/february-2025

[17] https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/company-insolvencies-january-2025

[18] https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Quarterly_registrations_of_new_businesses_and_declarations_of_bankruptcies_-_statistics

[19] https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/company-insolvencies-january-2025/commentary-company-insolvency-statistics-january-2025